Our journey through the world of soccer hatred has finally arrived at the spiritual home of soccer, the place many people think of first when they think of the sport — Brazil. No country has won more FIFA World Cups (five) than Brazil, which has produced a seemingly endless list of exceptional players, including Ronaldo, Ronaldinho, Neymar, Romario, Rivaldo, Kaka, Socrates, Garrincha, Dani Alves, Thiago Silva, Marcelo, Rivellino, and, you know, motherfucking Pele. Perhaps more importantly, Brazil has become the bastion of the “Beautiful Game,” embracing an artistic style of play that has captivated fans across the globe for decades. As much as the soccer scene in Brazil is influenced by the “samba” and “carnival” culture in the country, the country as a whole is influenced by soccer. The passion Brazilians have for the game is largely unmatched. In 1950, nearly 200,000 people watched Brazil choke away the World Cup Final to Uruguay in a match that was so traumatizing, the national team changed its uniform (adopting the popular canary yellow, blue, green, and white scheme we know today). In 2014, fans were openly crying in the stadium as Brazil was humiliated 7-1 by Germany in the World Cup semi-final. Brazilians are passionate and invested in the sport they have largely been considered to be the best at in the world.

But while many people know the Brazilian national team, nowhere near as many are familiar with Brazil’s club soccer scene, which has produced some of the best and most followed teams in the sport’s history. Brazil has also played host to the largest club soccer match in history — an attendance of 194,603. Brazil is massive — it’s the largest country in Latin America, the fifth-largest in the world (just behind the U.S. and China), and the sixth-most populous in the world (only the U.S. has a larger population in the Western Hemisphere). That population is divided into 26 states, each with its thriving and competitive soccer league to go along with the main national league. Soccer has been played in Brazil for more than a century, during which time Brazilian clubs have racked up 20 Copa Libertadores titles, the second-most of any country. Brazil is also the only country to see ten different clubs become South American champs. All of those decades of competition have also festered some intense hatred, leading to major rivalries between clubs from the same state. Given Brazil’s size, passion for the game, success at it, and lengthy history with the sport, that means there are A LOT of famous rivalries.

I knew that when I put the two rivalries per country limit (meant to increase diversity and not have a few countries dominate) in for this experiment, there would be some tough breaks. I’ve already had to exclude some major rivalries — the Manchester Derby, Madrid Derby, Merseyside Derby, and Derby d’Italia to name a few — due to this rule. But holy shit did those cuts pale in comparison to having to narrow down Brazil’s list of legendary rivalries down to just two. Not only do these states include several teams with lengthy histories, passionate fan bases, and intense hatred, but many of those teams have rivalries with multiple clubs. Sometimes, it’s tough to judge which rivalry is the most fierce for one particular club. However, through my research, I came to a consensus that some rivalries stood out more than most and I was able to cut down the list to… three. Each of these three are generally considered to not just be the best in Brazil, but also among the best in the world. Each has been listed in Top 10 lists from various publications. Each has compelling and justified reasons for making the cut. Each deserves to qualify for the World Cup of Hate. Eliminating one of these three was by far the hardest decision I made during this entire process. No matter what, my decision was going to be controversial. I will talk about each of these three rivalries, starting with the two that managed to survive.

Paulista Derby (Brazil)

Sport Club Corinthians Paulista vs. Sociedade Esportiva Palmeiras

“In the line-up of the world’s greatest derbies, Corinthians against Palmeiras in Sao Paulo ranks as high as any for passion and history.” — Joshua Law, writer for These Football Times

Even among the many great Brazilian sports rivalries, the Paulista Derby stands out for its ferocity, competitiveness, and relevance to the country’s soccer history. Ever since Corinthians and Palmeiras first clashed more than a century ago, their matchups have decided local, state, national, and continental supremacy more than most others.

Sao Paulo is huge — it’s the most populous city in Brazil (nearly doubling second place Rio de Janeiro), the Americas, and the Western and Southern hemispheres, as well as the biggest Portuguese-speaking city in the world. The greater Sao Paulo area is also the fifth-largest in the world, above places like Mexico City, New York City, Osaka, and Beijing. If something is able to grip the city and divide its inhabitants into two even sides, it must be pretty powerful. Soccer is definitely capable of doing that, with each of the main clubs garnering huge support bases. Along with Rio de Janeiro, the state of Sao Paulo had the most clubs (four) among the founding members of the Clube dos 13 — a group of the biggest and most influential clubs in Brazil. Each of those four clubs — Santos, Sao Paulo, Palmeiras, and Corinthians — share rivalries with each other, particularly the latter three clubs based in the city of Sao Paulo. But with all due respect to Santos and Sao Paulo, the hatred between Corinthians and Palmeiras is on another level.

Palmeiras and Corinthians had already been playing for more than a decade before Sao Paulo was founded. Furthermore, during the decades since then the Paulista Derby has decided state, regional, and national titles, and been played at late stages in the Copa Libertadores. It can easily be argued that no other Brazilian soccer rivalry has this many major trophies involved. That’s part of what sets this rivalry apart. Don’t get me wrong, it has as much passion and hatred as you’d like. Each fandom has roots in different societies and cultures, which adds a unique aspect to proceedings. But despite the great anger and violence that can erupt during clashes between Corinthians and Palmeiras, the ferocity comes from the competition on the field, where silverware can be won or lost with one kick of the ball

HISTORY:

At the start of the 1910’s, soccer was an elitist sport in Brazil, with the best clubs largely fielding wealthy foreigners and the lower class representing the smaller teams. In 1910, London-based club Corinthian FC toured the country, making a stop in Sao Paulo for a match. Among those in attendance was a group of five workers for the Sao Paulo Railway, who were inspired to create a club of their own. The next night — underneath the glow of an oil lamp on Rua Jose Paulino (“Immigrants Street”) — they took inspiration from the team they had watched and created Sport Club Corinthians Paulista. Corinthians did well over the first few years and eventually made the Liga Paulista, winning the Sao Paulo State Championship in 1914. That was the same year a group of Italian clubs had also arrived to tour Brazil, making stops in Sao Paulo. That inspired members of the prominent Italian immigrant community in the city to make a club of their own. Called Palestra Italia, the club was also used by the Italian Consulate in Sao Paulo to spread the word to the Italians in Brazil that Italy had been unified. By doing so, they also unintentionally branded Palestra as the Brazilian club for Italians to cheer for. Oh, and it didn’t help that those Italians used to be members of Corinthians, instantly drawing battle lines.

It took three years before these two sides met for the first time, but it was apparent that this could be a great rivalry. In 1917, Corinthians was the defending Sao Paulo champs and had a three-year, 25-game unbeaten streak. But that didn’t matter in the semi-finals of that year’s state tournament, when Caetano scored a hat trick to lead Palestra to a 3-0 upset win. After another match (a 3-1 Palestra win), the two sides met again in 1918. According to legend, on the day of the game some Palestra players passed an area where Corinthians players were eating, throwing an ox bone at them. The bone had the message “Corinthians is chicken soup for Palestra” written on it. That pissed Corinthians off, with the club twice rebounding from deficits to produce a 3-3 draw. Since then, Corinthians has kept the bone in their trophy room. In 1921, a trophy was at stake when Corinthians met Palestra on Christmas Day — in the final match day of the Paulista Championship. With Corinthians needing a win to claim the title, Palestra denied their inner-city rivals with a 3-0 victory, with the crown going to Paulistano instead. It was after this point that everyone in Sao Paulo knew the Paulista Derby was real and here to stay.

Unfortunately for Palestra, that choke job seemed to unlock something within Corinthians. Starting in 1922 — the Centennial of Brazilian Independence — Corthinians got back on top of the Paulista Championship, a title they proceeded to win in 1923 & 1924 as well. Corinthians winning the championship sort of became a trend over the next couple of decades, with the club claiming Paulista three-peats from 1928-30 and 1937-39. This isn’t to say that Palestra didn’t have any success in this time — they claimed a handful of championships as well, including their own back-to-back-to-back run from 1932-34. That middle season, 1933, was a particularly major year for Palestra and the Paulista Derby. First, their home ground, Estadio Palestra Italia, became Brazil’s first stadium with concrete grandstands and barbed-wire fences. Then, on November 5, Palestra unleashed hell on Corinthians. Romeu Pellicciari scored four times and Imparato added a hat trick as Palestra thrashed Corinthians 8-0, the largest margin of victory to date between the two rivals. The humiliating defeat caused Corinthians’ president to resign and its fans to set the club’s headquarters on fire.

Things didn’t get better when, four years later, Corinthians and Palestra met in a three-game series to decide the 1936 Paulista Championships (if you do the math, that reads as deciding the 1936 title in 1937 — that’s correct and I have no idea why). The best Corinthians could do was a 0-0 draw in the second game, as two Palestra wins gave them the title. If you thought the year thing was weird, get ready for 1938, the second “back” of Corinthians’ third back-to-back-to-back run since 1920. The season was suspended from April to September due to the national team’s preparation for that year’s World Cup. Not wanting to waste several months, an extra tournament was created to fill the teams’ schedules. Naturally, Palestra and Corinthians met in the final, with the former winning. Given that Corinthians won the actual regular season title, rival fans contend to this day that winning the extra tournament should count as a championship as well. Speaking of extra tournaments, that same year, fellow local club Sao Paulo FC was going through a financial crisis. So they created a four-team tournament involving themselves, Corinthians, Palestra, and fellow Sao Paulo club Portuguesa in order to raise money. Palestra and Corinthians faced off in the semi-finals, a game known as “Jogo das Barricas.” In a match which didn’t even last the usual 90 minutes due to lack of daylight, the score ended 0-0, with Corthinians advancing due to having taken the most corner kicks. Corinthians would go on to win the tournament.

The 1940’s would prove to be significant for both clubs, in different ways. At the start of the decade, the city of Sao Paulo inaugurated Pacaembu Stadium, holding a tournament to break in the new venue. Of course, Corinthians and Palestra would meet in the finals, with the latter winning the first trophy awarded at the stadium (to go along with their league championship). Corinthians would bounce back, winning the 1941 title. A year later, the new stadium would begin hosting the annual Taca Cidade de Sao Paulo, which would last through 1952. Corinthians would win the first, last, and an overall majority of those tournaments. However, that 1941 league championship would be the only one Corinthians claimed for an entire decade. 1942 would be much more significant for another reason — with World War II ongoing, Brazilian president Getuilo Vargas issued a decree banning any organization from using names related to the Axis Powers. That included Palestra, who had to change from Palestra Italia to Palestra Sao Paulo. However, this wasn’t enough for officials, who threatened to force the club to forfeit its assets unless they completely changed their name. This came at a time when Palestra was unbeaten in the league and could clinch the title with a win over Sao Paulo, who were trying to seize some of those assets. The night before the match, the Palestra board of directors met, with Dr. Mario Minervino saying, “They don’t want us to be Palestra, so then we shall be Palmeiras — born to be champions.” The following day, the new Palmeiras beat Sao Paulo 3-1, with the latter leaving the field after Palmeiras was awarded a penalty. Newspapers famously ran the headline: “A Leader Dies, A Champion is Born.” However, Palmeiras couldn’t claim to be an unbeaten champion — they lost the final game of the season to (who else?) Corinthians.

Palmeiras’ “Arrancada Heroica” triumph wouldn’t be the last time politics got involved in one of their matches. In 1945, Palmeiras and Corinthians came together in a rare moment for an even rarer cause: a fundraiser for the Brazilian Communist Party. Corinthians would triumph 3-1, with the match being known as “O Jogo Vermelho” and even being the focus of a book by politician Aldo Rebelo. It was also rare in being positive for Corinthians during this era. Palmeiras would add two more championships in the 1940’s, record the second-biggest victory in rivalry history (6-0 in 1948), and then claim the 1950 Paulista Championship to pull within one of Corinthians’ record total. But, Corinthians was about to wake up — with a vengeance. In 1951, Corinthians absolutely torched their Paulista competitors, scoring 103 goals in 30 games (an average of 3.43 goals per game) en route to claiming their first title in a decade. Corinthians would win the title again in 1952 and 1954, and do something unique in between. In 1953, Corinthians was invited as a replacement in the Small Club World Cup, a precursor to competitions like the Intercontinental Cup and Club World Cup. They won the title by beating the likes of Barcelona, Roma, and a selection of players from the host city, Caracas, Venezuela. But Corinthians can’t claim the first such title among Paulista Derby clubs. Two years earlier, Palmeiras took part in the Copa Rio, a Brazil-organized tournament including Juventus, Nacional, Sporting, Red Star, and Nice. Palmeiras beat Juventus in the final to claim the tournament, which would be shut down after the following year (which saw Corinthians lose in the final). There’s a decades-long process behind it, but the Copa Rio is pretty much considered the first “Club World Cup.”

Those tournaments were also the precursor to more permanent national and continental competition. Though Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro were considered the two top states in Brazilian soccer, there was still no true national champion. However, as the 1950’s came to an end, CONMEBOL (the governing body of South American soccer) decided to put together a continental tournament (which would become the Copa Libertadores), starting in 1960. Needing a representative — and with advancements in air transport making it easier to traverse the world’s fifth-largest country by area — officials organized the first ever national soccer league in Brazil in 1959. The champions of each state league would qualify for the following year’s Taca Brazil, with the winner going to the Copa Libertadores. Although they didn’t take part in the original competition, Palmeiras won that year’s Paulista title to reach Taca Brazil in 1960. They also won that to qualify for the second ever Copa Libertadores, making it all the way to the final before losing to defending champs Penarol. Palmeiras would get another crack at the South American title in 1968, splitting two games with Estudiantes. Although Palmeiras had a 4-3 advantage on aggregate goals scored, the only result that counted was wins and losses, meaning a third match would be needed. Estudiantes won 2-0 to break hearts in Brazil. Palmeiras might have gotten more opportunities at international competition had they not run into Santos, a fellow Sao Paulo club which would win two Copa Libertadores titles and six Brazilian national league crowns that decade, thanks in part to a young player named Pele.

As for Corinthians? Well, they were in quite a drought. Some years, they would get close. Others, they would straight up stink. Either way, Corinthians hadn’t won a trophy since 1954. Meanwhile, Palmeiras would win more Paulista Championship crowns, surpassing Corinthians’ record in 1972. Another title came in 1974, the 20th anniversary of Corinthians’ last triumph, with Palmeiras beating Corinthians in the final. After the game, Palmeiras fans chanted “Zum, zum, zum, it’s 21,” in reference to another year being added to the drought. Things reached a peak for Palmeiras with another title in 1976, putting them three above their rivals. Finally, in 1977, the drought finally came to an end as Corinthians won their first Paulista title in 23 years. Another championship would come two years later, though not without controversy. The Palista Championship format was weird and confusing, but that didn’t stop Palmeiras from going off on a huge run. So allegedly in an attempt to cool off their rivals, Corinthians president Vincente Matheus refused to play a double round as scheduled (due to concerns over his club’s income being harmed), leading to a lawsuit that stopped all games for several months. By the time things were reset, Palmeiras had indeed slowed down, with Corinthians coming out on top when the clubs played in the semi-finals, en route to the 1979 title.

Corinthians would win three more championships in the decade (taking back their record in the process), though they could’ve won another had it not been for an extra time victory by Palmeiras in the 1986 semi-finals. But that, as well as a 5-1 victory over their rivals that year (avenging a 5-1 Corinthians win four years earlier), were the only highlights for Palmeiras, which was in a slump similar to that of Corinthians the previous decade. That drought could’ve ended in 1989, with Palmeiras needing a win over already-eliminated Corinthians on the last day to reach the final of the Brazilian championship (which had been expanded to include non-state winners years earlier). However, a 1-0 win by Corinthians extended Palmeiras’ drought. Corinthians also won their first Brazilian national title in 1990, claiming the Supercopa do Brasil the following year. But just when it seemed like Corinthians would start pulling away from their rivals, Palmeiras would get a much-needed injection from an unlikely source. In 1992, Palmeiras signed a lucrative sponsorship deal with Italian dairy giant Parmalat (a unique one for Brazilian clubs), quickly becoming one of the richest teams in the country. This also helped build Palmeiras’ reputation as a “club of the rich” (and Corinthians as a “club of the people” by contrast), despite the two clubs and their fanbases being similar economically. But no one doubts that the deal allowed both Palmeiras and Corinthians to be good at the same time for the first time in decades.

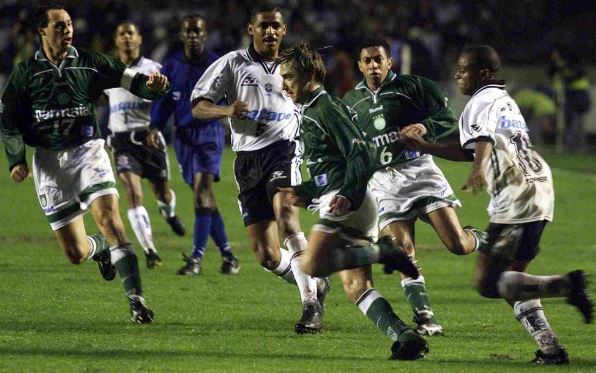

Things got started right away, with Palmeiras winning the Paulista title the first year after the partnership, defeating Corinthians in the final no less. That, coupled with a national league title, gave Palmeiras a domestic double. That feat would incredibly be repeated in 1994, with Palmeiras edging out Corinthians again, this time for the Brazilian crown. Corinthians would strike back the following year, beginning a decade-long stretch of winning the Paulista crown every other year. Corinthians would also earn its first Copa do Brasil title in 1995. Palmeiras would get their own crown three years later, but by that time Corinthians had caught up in the national division, winning back-to-back league titles in 1998-99. Also, the competition between the rivals had reached the international stage, arguably hitting the peak of their hatred at the turn of the century. In 1999, Palmeiras and Corinthians met in the quarter-finals of the Copa Libertadores. The two traded 2-0 results, with Palmeiras narrowly advancing on penalties. They would carry that momentum all the way, topping Deportivo Cali on penalties in the final to claim their first ever South American championship. Corinthians would get some measure of revenge, beating Palmeiras in the Paulista final days later. Late in the second leg, with the result all but decided, Edilson began to juggle on the field, which led to a harsh tackle and eventual brawl between both clubs, forcing the referee to abandon the match. Tensions kept going the following year, when the two clubs again met in the Copa Libertadores, this time in the semi-finals. In a fantastic two-game tie that saw a combined 12 goals, penalties were needed again, with Palmeiras once again coming out on top (though they would lose in the final to Boca Juniors). Meanwhile, by winning the national league, Corinthians got to take part in the inaugural FIFA Club World Cup (which Brazil hosted). Against the likes of Real Madrid, Manchester United, and Raja Casablanca, Corinthians beat Vasco da Gama to claim an international trophy of their own.

As quickly as things got good, just as quickly did things take a nosedive. Palmeiras’ famous sponsorship with Parmalat ended in 2000, which got rid of a huge source of income. Despite making the Copa Libertadores semi-finals in 2001, Palmeiras had a dreadful season in 2002, which ended with the club being relegated to Serie B. Though they would climb back up the following season, it was Corinthians’ turn to go through difficulties. A lack of funds and bad administration decisions led to a controversial deal with Media Sports Investment, which was part of the reason Corinthians were relegated in 2007 (two years after winning the league title due to a match-fixing scandal). Corinthians came back the following season and won their third and most recent Copa do Brasil crown in 2009. Three years later, it was Palmeiras who once again was relegated to Serie B, a collapse made more incredible by the fact that they had won the Copa do Brasil that season, going unbeaten in the process. That same year, Corinthians finally broke through on the international level. Like their rivals, Corinthians did not lose a single game during their Copa Libertadores campaign, taking out Boca Juniors in the final to win their first South American championship. They then kept that momentum going in the Club World Cup, beating out the likes of Chelsea, Monterrey, and Al Ahly for the title.

Both clubs spent the mid-2010’s trying to live up to the mantra, “anything you can do, I can do better.” In 2014, Corinthians introduced their brand new Arena Corinthians stadium. The next year, Palmeiras debuted their own brand new Allianz Parque, though the Paulista Derby debut at the stadium came with fears of violence that saw officials consider a ban on opposing fans. That didn’t happen and Corinthians actually pulled off the upset. Although Palmeiras would win the Copa do Brazil, Corinthians would eliminate Palmeiras from a tournament in penalties for the first time ever (in the Paulista Championship). The two clubs’ battles would also decide the national championship, with Corinthians and Palmeiras trading the crown of Brazilian soccer back-and-forth from 2015-18. That last year also saw the first championship final between the two rivals in 19 years, with Palmeiras winning the Paulista title 1-0. The COVID-19 Pandemic would mark the start of a new era for Palmeiras, who would win their fourth and most recent Copa do Brasil trophy in 2020, the same year Palmeiras topped Corinthians for the Paulista title in front of no fans. Palmeiras would complete the historic treble in the 2020 Copa Libertadores Final, with Breno Lopes scoring the only goal nine minutes into stoppage time against Santos to give Palmeiras its second South American crown. They didn’t have to wait long for their third — Palmeiras beat Flamengo 2-1 in extra time of the following final to become just the sixth ever club to win back-to-back Copa Libertadores titles. Throw in a national championship in 2022 and the second of three Paulista titles in four seasons this year and Palmeiras is on its most successful period ever. But if you’ve learned anything about this rivalry, we’re likely about to see Corinthians make another run for local and national supremacy.

MAJOR ON-FIELD MOMENTS:

AN OX-PICIOUS BEGINNING

Two games, two wins for Palestra. That was how the Paulista Derby began. Thus, the day the two squads were to play a third time, Palestra were confident they would make it three for three. They were so confident, when they passed an area where Corinthians were having lunch, they threw an ox bone at their opponents. Written on the bone was the message, “Corinthians is chicken soup for Palestra.” Naturally, Corinthians didn’t take that well. Twice during the match, Palestra took the lead; twice, Corinthians came back to tie the game. In the end, the “three” in the match ended up going to both goal totals, with the new rivals drawing 3-3. Since then, Corinthians have kept that ox bone in their trophy room, a symbol of the sparked rivalry.

EARLY TITLE DECIDERS

In the first few decades of the Paulista Derby, Palestra and Corinthians met late to decide the Paulista Championship. In 1921, all Corinthians needed was a win to claim the title (and a draw to tie). However, Palestra beat them 3-0 in the final match to deny them the honor. In 1936, the two squads met in the final of the competition. The first game saw Palestra win 1-0 after their rivals left the field in the second half due to complaints over a foul. A 0-0 draw and 2-1 Palestra win gave them the crown. Two years later, an extra tournament was held due to Brazil’s involvement in the 1938 World Cup. Corinthians and Palestra met in the final, with the latter coming out on top after a 0-0 draw and 2-1 victory, although it’s not considered a league title.

THE GREAT EIGHT

In 1933, Palestra and Corinthians met for a match that would count for both the Paulista title and Rio-Sao Paulo Tournament. It was expected to be an important result, but no one could have foreseen what was to come. Romeu Pellicciari scored four goals, while Imparato added another, as Palestra absolutely demolished Corinthians 8-0. The ass-whooping remains both the most lopsided result in the history of the Paulista Derby, but also the biggest defeat ever suffered by Corinthians. As one might expect, shit hit the fan after this. Not only was the president of Corinthians forced to resign, but after the match a mob of angry fans stormed the club’s headquarters and set fire to the building itself. Corinthians have yet to avenge this loss.

BARRICAS E VERMELHOES

Two of the most unusual sets of circumstances to surround a Paulista Derby match took place within seven years of each other. In 1938, Sao Paulo FC was in need of finances and created a four-team tournament involving Corinthians, Palestra, and Portoguesa to raise money. Palestra and Corinthians would face off in the semi-final known as the “Jogo das Barricas,” which ended 0-0. Corinthians would advance due to having taken more corner kicks during the match. Seven years later, the two rivals would be involved in another match to raise money, this time for the Brazilian Communist Party. Palmeiras would win 3-1 in a match that would be documented in the book Palmeiras x Corinthians 1945: O Jogo Vermelho, written by politician Aldo Rebelo.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

1942 was arguably the most important year in Palmeiras’ history. For starters, they didn’t have that name to start the season. Palestra Italia was forced to change its name due to a new law in place banning the use of names related to Axis powers. Threatened to be shut down and have its assets seized right before the game that would clinch the Paulista title, Palestra adopted the new name of Palmeiras, then beat Sao Paulo 3-1 to claim the championship. That was the second-to-last match of the season, with Palmeiras having an unbeaten record of 17-0-2. The last match of the year would be against Corinthians. While their rivals would still be champs, Corinthians were able to at least spoil the party, winning 3-1 to prevent an unbeaten season.

FOURTH CENTENARY CHAMPIONSHIP

The 1954 edition of the Paulista Championship was an important one for all clubs involved. That year marked the fourth centenary of the city of Sao Paulo (which was founded in 1554), with celebrations across the region. Thus, winning that year’s league title would be extra special. Naturally, it came down to Corinthians and Palmeiras, with the latter having an advantage going into a late season matchup. Palmeiras needed to win, while a draw was enough for Corinthians to win the title. The latter is exactly what happened, with Corinthians scoring early then holding off a late rally by Palmeiras to secure a 1-1 draw and claim the 400th anniversary title. However, that would be Corinthians last championship victory for a long time (though not 400 years).

A FORGOTTEN GEM

While the first 1971 Paulista Championship clash can’t claim the most goals in a single Paulista Derby match (that honor goes to a 6-4 Corinthians win in 1953), this fantastic showdown was still filled with plenty of scoring. Often forgotten due to being old and not for a trophy, this game is one of the best in rivalry history. Palmeiras jumped out to a 2-0 halftime lead thanks to Cesar Maluco, before Corinthians tied the score at 2-2. Palmeiras got back in front a minute later, only for Corinthians to equalize again. Then, with just two minutes left, Mirandinha netted the winner for Corinthians, with the match ending 4-3. Arguably the best played match in rivalry history, the loss to Corinthians would haunt Palmeiras, as they would lose the league title by three points.

MAKE IT 21

In 1974, Corinthians made it back to the Paulista Championship final, so close to ending their 20-year title drought. Standing in front of them were their rivals, with Palmeiras having broken Corinthians’ total league title record just two years earlier. After a 1-1 draw at home, Corinthians headed into their rivals’ stadium, needing a win to finally end the drought. Unfortunately for them, they would not pull off the upset, as Palmeiras won 1-0 to move two league titles clear of Corinthians in the standings of history. To add insult to injury, the just over ten thousand fans inside Palmeiras’ stadium began chanting “Zum, zum, zum, it’s 21,” referencing that it would be at least another year added to Corinthians’ two decades without winning a single trophy.

SOME DROPS IN THE DROUGHT

Palmeiras was still in its own title drought in 1986, though the year still had some highlights. First, Palmeiras avenged a 5-1 defeat to Corinthians four years earlier with their own 5-1 victory. Then, the two rivals met in the semi-finals of the Paulista Championship. A controversial first leg saw Corinthians walk away with a 1-0 win. The second leg was scoreless until late in the game, when Palmeiras finally found the back of the next to force extra time. It was all Palmeiras after that, with the club scoring a second goal in the overtime period. Palmeiras would put the game away in style, with Eder scoring an Olympico to make it a 3-0 final. While Palmeiras would not end the drought that year, they at least scored some big wins over their rivals to salvage things.

FINALLY, WATER

Seven years later, Palmeiras was once again back in the Paulista Championship final with another chance to end the drought. Naturally, Corinthians stood in the way. Like the showdown above, Corinthians won the first leg 1-0, with Viola, the goalscorer, imitating a pig (which had recently been taken on by Palmeiras as a club symbol) in mock celebration. Also just like in the 1986 matchup, Palmeiras needed a win to keep their hopes alive, and got it with a 3-0 score in regulation. However, aggregate was not taken into account at the time, with only the results mattering. So, once again, extra time was needed. Once again, Palmeiras managed to come through in the overtime frame, converting a penalty for the 1-0 advantage and the league title.

THE LIBERTADORES PENALTIES

Arguably the peak of the Paulista Derby came at the turn of the century, when Corinthians and Palmeiras met in the knockout round of back-to-back Copa Libertadores. In 1999, the two faced off in the quarter-finals, with both clubs exchanging 2-0 wins. The second leg took place in Corinthians’ stadium, which should have given them the advantage in penalties. But Palmeiras ended up winning 4-2, then going on to win their first South American championship. The next year, the stakes were raised when the clubs had a rematch in the semi-finals. A 4-3 Corinthians win in the first leg was followed by a 3-2 win by Palmeiras at home in the second leg. Though these penalties were closer, the result was the same — Palmeiras won 5-4 to reach the final.

TALK SHIT, GET HIT

Just a few days after Palmeiras won the 1999 Copa Libertadores, they found themselves in another final — the Paulista Championship. Waiting for them were the rivals they had beaten in on penalties in the above quarterfinals: Corinthians. However, with fresher legs due to not having to play extra games (and not having to come down from such an emotional high), Corinthians were able to get their revenge. Corinthians won the first leg 3-0 and, despite a rally by Palmeiras, were cruising to the title with the score at 2-2 with about 15 minutes left. That’s when Edilson taunted Palmeiras by juggling the ball in the middle of the game. Junior and Pablo Nunes went after Edilson, igniting a massive brawl that led to the game being called early.

STATISTICS:

HEAD-TO-HEAD RECORD

Corinthians: 129

Palmeiras: 133

Draw: 113

LEAGUE CHAMPIONSHIPS

Corinthians: 7

Palmeiras: 11 (record)

COPA DO BRASIL

Corinthians: 3

Palmeiras: 4

CAMPEONATO PAULISTA

Corinthians: 30 (record)

Palmeiras: 25

TACA CIDADE DE SAO PAULO

Corinthians: 5 (record)

Palmeiras: 4

TORNEIO RIO — SAO PAULO

Corinthians: 5 (record)

Palmeiras: 5 (record)

COPA LIBERTADORES

Corinthians: 1

Palmeiras: 3

RECOPA SUDAMERICANA

Corinthians: 1

Palmeiras: 1

FIFA CLUB WORLD CUP

Corinthians: 2

Palmeiras: 0

NOTABLE FIGURES:

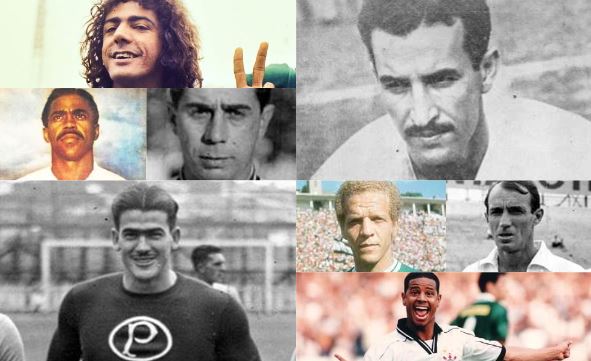

CLAUDIO

Claudio is the all-time highest scorer in the history of the Paulista Derby (with 21 goals) and was always able to find the back of the net, no matter who he played for. He moved to Palmeiras in 1942 and was actually the first goal scorer for the club under its current name. However, two years later he was suiting up for Corinthians, where he stayed for the next 13 years. Kicking off his scoring against his former club, Claudio would go on to net 306 goals in 554 games for Corinthians. Claudio was also a strong leader, so much so that his nickname was “Manager.”

HEITOR

Ettore Marcelino Dominguez, known much better as Heitor, retired nearly 100 years ago. Yet, he remains Palmeiras’ all-time leading scorer with a whopping 327 goals in 358 games. That’s surprisingly close to doubling the total of the second-highest goal scorer’s total of 180. Heitor is also Palmeiras’ top scorer in the Paulista Derby, talling 16 goals. With Heitor leading the way, Palmeiras (then known as Palestra) won three Paulista Championships. Heitor also made waves with Brazil’s national team, winning the third and sixth Copa Americas in 1919 and 1922.

BALTAZAR

Although in the Bible, Balthasar was the wise man that brought frankincense for baby Jesus (and Melchior was the one who brought gold), legendary Corinthians striker Baltazar was known as :Cabecinha de Ouro” (“Golden Head”). Baltazar definitely used his head a lot while in front of goal, scoring 267 times in 401 appearances for Corinthians. He’s also the second-highest goal scorer in the history of Paulista Derby, finding the net 20 times. Baltazar is also the only player to score in two different opening World Cup matches, doing so in 1950 and 1954.

CESAR MALUCO

Although he’s far away from Heitor’s insane record of 327 goals, Cesar Maluco still holds the second place spot with 180 goals scored for Palmeiras. Maluco was a key part of Palmerias’ last strong era before their lengthy title drought from the late 1970’s to early 1990’s. Maluco scored 15 goals to help Palmerias win the Brazilian national championship in 1967. He was also part of two Paulista Championship-winning squads for Palmeiras, including the famous 1974 team that prevented Corinthians from snapping their (at the time) 20-year titleless drought.

LUIZINHO

While Palmeiras currently has the most wins in the rivalry, Corinthians can boast having the three top goal scorers in Paulista Derby history. After Claudi and Baltazar comes Luizinho, who scored 19 goals in rivalry matches. Those goals contributed to his total of 172 for Corinthians across 605 appearances. Luizinho spent all but one year of his 19-year career with Corinthians, winning three Paulista Championships. Although he’s considered one of Corinthians’ best players ever, Luizinho unfortunately had a lot of his career happen during their lengthy drought.

ADEMIR DA GUIA

Although Corinthians has the top three scorers in Paulista Derby history, Palmeiras has the player with the most appearances. That would be Ademir da Guia with 57 (as well as 153 career goals, the third-most in Palmeiras history). Nicknamed “O Divino” (“The Divine One”), de Guia is considered one of Palmeiras’ all-time best players, making 366 appearances for the club over 16 years. Da Guia won both the Paulista Championship and Brazilian national title five times across his career, which ended in 1977 in a match between Palmeiras and Corinthians.

RIVELLINO

Ask Corinthians fans who their club’s best ever player is, and they’ll probably give one of three names: Claudio, Socrates (no not that one), and Rivellino. Known for his iconic mustache, hard shots, long-range kicks, and a move he invented called the Elastico (which would be more popularized by the likes of Ronaldinho), Rivellino lit up the field for Corinthians, though his time with the club coincided with the club’s lengthy drought (he became kind of scapegoat as a result). Rivellino is still considered one of the best Brazilian players to ever take the field.

OBERDAN CATTANI

Although goal scorers have gotten plenty of love so far, it’s time to shine the spotlight on a goalkeeper, particularly one who looked like a young Vito Corleone crossed with Superman. Oberdan Cattani is a Palmeiras legend — the son of Italian immigrants and former truck driver made 351 appearances over 14 years for the club. Known for his great strength, elasticity, and large hands, Cattani should be more popular. But, his prime (when he would’ve been called up to Brazil’s national team), coincided with World War II, when there were no World Cups.

MARCELINHO CARIOCA

Marcelinho Carioca was a controversial player, but also an incredibly successful one for Corinthians. In fact, no player has won more trophies (eight) in club history. That includes the 1998 and 1999 Brazilian championships and 2020 FIFA Club World Cup. He also finished with 206 goals in 420 matches across three different stints with Corinthians. However, Carioca was also well known for his off-field antics and disputes with managers. That includes Vanderlei Luxemburgo, who has been in charge of both Corinthians and Palmeiras several times.

EDILSON

While probably the least productive person on this list, Edilson nonetheless was a significant contributor to this rivalry. Not only did he play for both clubs (making the move from Palmeiras to Corinthians in 1997), but he also sparked one of the most infamous moments in Paulista Derby history. After all, it was he who started to juggle on the field during the final of the Paulista Championship in 1999, taunting Palmeiras and igniting a massive brawl between the clubs that caused the match to be abandoned with nearly 15 minutes left remaining in regulation.

FAN INVOLVEMENT:

Sao Paulo is the most populous state in Brazil and (along with Rio de Janeiro) has always been considered among the best/most successful at soccer. Therefore, there are plenty of people to cheer for their favorite club and boo their rival. While Palmeiras was initially heavily supported by Brazilians of Italian descent, the fan base is much more diverse today, with pockets of fans being spread out across the country. The biggest, of course, is in Sao Paulo, with the largest group being the Mancha Alvi-Verde (White and Green Stain). Noted journalist and Palmeiras fan Joelmir Beting once famously wrote, “it is unnecessary to explain the emotion of supporting Palmeiras to its fans, and impossible to do it to the non-fans.” That quote has been plastered on the walls of Allianz Parque’s home dressing room.

As for Corinthians, their fans are so passionate that the club itself made a tribute documentary for them called Faithful, which highlighted the support the club received during their relegation in 2007. The film was the same name of the supporters in general (“Feil” in Portuguese). While, like Palmeiras, Corinthians has pockets of fans across Brazil, including during the country’s famous Carnival festivities. In fact, a Corinthians fan branch is Gavioes da Fiel, a samba school that has won the Carnival of Sao Paulo Parade contest four times, the most of any group affiliated with a soccer team. But fans also travel from Sao Paulo as well — a famous incident called “Invasao Corinthiana” (“the Corinthian Invasion”) saw more than 70,000 Corinthians fans travel to a match against Fluminense in 1976.

With this amount of passion, sparks naturally fly whenever these two fan bases clash, with incidents of violence sometimes surpassing the action on the field. But sparks can also fly in other ways. Much like another rivalry mentioned a couple of parts ago, the Paulista Derby was the setting of a theatrical adaptation of Romeo and Juliet: 2005’s O Casamento de Romeu e Julieta (Romeo and Juliet Get Married). But that’s not the most famous film centered around the rivalry. That honor goes to Mazzaropi’s 1967 classic O Cristiano, about a barber and Corinthians fan who does not charge services from other Corinthians fans and does not like to provide services to Palmeiras fans.

SUMMARY:

Given Brazil’s lengthy history, success, and overall impact on soccer, it’s no surprise that it has some rivalries that can compete with the best in the world. That’s certainly the case with the Paulista Derby, as Corinthians and Palmeiras have a deep-rooted hatred from more than a century of fierce competition, which more often than not influences who wins a trophy.

Of course, that’s just one of the many intense rivalries across this soccer-crazed country, let alone involving those two teams. With only one spot left in the World Cup of Hate for Brazil, the choice to fill that spot is incredibly difficult, given that the country is packed full of century-long, hate-filled, blood and championship-soaked rivalries that could give many of the already qualified rivalries a run for their money. In the end though, a decision had to be made. This is it.

Grenal (Brazil)

Gremio Foot-Ball Porto Alegrense vs. Sport Club Internacional

“Rio Grande do Sul has the firm positioning of its citizens as a cultural mark. Either you are this or that, either left or right, either Brizola or Pedro Simon. In this context, Gremio and Internacional complete each other. Neither Gremio nor Inter is bigger, but the GreNal is the greatest product of Rio Grande do Sul. It comes from everything being polarised.” — Jeremias Wernek, sportswriter for Universo Online

Grenal is one of the fiercest, most competitive, oldest rivalries in Brazil, South America, and the entire world. When Gremio and Internacional take the field, they represent a sort of Yin and Yang, facing off as diametrically opposite as can be, dividing the state of Rio Grande do Sul in half in a clash of culture, economics, and way of life.

While even some of the fiercest rivals can find some common ground and similarities, that is not the case with Internacional and Gremio. Rarely have clubs been such polar opposites — from their identity and fan base to their values to even the way they look. Everything about these two rivals clashes whenever they face off. It doesn’t exactly hurt the rivalry that many of their battles have come in the chase of local, national, and (more recently) continental supremacy. This kind of conflict has origins dating back to the very foundation of the clubs. Grenal (which refers to the first three letters of “Gremio” and last three letters of “Internacional”) is also unique in that it began with something rare for a rivalry of this nature: a complete and utter annihilation.

HISTORY:

Although Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro are the two most successful and well-known states in Brazil when it comes to the sport, the first professional soccer team was founded in Rio Grande do Sul in 1900. Three years later, that club, Sport Club Rio Grande, played an exhibition match in Porto Alegre, where an entrepreneur named Candido Dias was in attendance. According to legend, the ball the players were using deflated and, as the only man in Porto Alegre with a soccer ball (remember, soccer was an elitist sport back then), Dias lent his ball to the players. After the match, he talked to them about how to start his own club. Just over a week later, Dias was among a group of 32 people who met at the Salao Grau restaurant and founded Gremio Foot-Ball Porto Alegrense. Their original colors were blue and a shade of brown known as havana. However, because of the scarcity of havana fabric, they later replaced it with black, adding white soon after to create their familiar “tricolor” combination. Their first match took place a year later, winning 1-0 and winning the Wanderpreis trophy. Gremio was not only able to get propped up quickly, but succeed so soon, because at the time soccer in Brazil was the realm of rich foreigners, largely German or English people (most of those at the founding meeting were part of the city’s German community).

That was the case for journalist Henrique Poppe Leao, who moved from San Paulo to Porto Alegre in 1901 and found it difficult to practice the sport. In 1909, he, along with his brothers Luiz Madeira Poppe and Jose Eduardo Poppe, decided to found their own club, one that would be open to players of all nations. The name, Sport Club Internacional, was a tribute to Sao Paulo International, a club from their hometown whose red (and black) colors they also borrowed. On July 18 that same year, Internacional held their first ever match — against Gremio. Originally, Gremio wanted to play their reserves, due to having another match to prepare for soon. However, Internacional wanted them at full force, a request Grenal would accept. What followed was not only a perfect metaphor for soccer in Brazil at the time, but one of the biggest destructions you’ll ever see in the sport. Spurred on by five goals from Edgar Booth, Gremio destroyed Internacional 10-0, which remains the largest margin of victory between the two rivals. The ass-whooping was so bad, at one point Gremio’s goalkeeper reportedly left the field to chat with fans during play. Incredibly, this isn’t even Gremio’s biggest ever win — that came in a 23-0 (seriously) drubbing of Sport Clube Nacional Porto Alegre three years later. However, unlike Nacional, Internacional would eventually prove to be much more of a threat to Gremio than they were in Match 1.

However, things would not get better immediately. The second ever Grenal was technically an improvement, though Gremio still won 5-0. The third match, however, was almost as bad as the first, with Gremio beating Internacional 10-1. That game was for the city championship of Porto Alegre, with Gremio completing an unbeaten title campaign. Internacional would at least get on the board with back-to-back unbeaten Porto Alegre championships in 1913-14. However, that first win over Gremio remained elusive. Finally, in 1915 (the seventh matchup of the rivalry), Internacional got in the win column against Gremio, coming out on top 4-1 in front of a feisty crowd that had become ravenous for a victory. Another first would come in 1918: the first major violent incident, which would be hard to top. With Gremio leading 1-0 in the 43rd minute, the ball went out of bounds. It’s important to note that, at this time, there was often nothing between the crowd and the side of the field. Amid a discussion over who had possession, a fight broke out between Internacional players and a group of Gremio fans. This sparked a riot involving players, fans, and officials that ended with around 100 people getting hurt and one man being arrested. That man was Manoel Costa, who stabbed one International player in the stomach and slashed another player’s leg. Costa was eventually put in a police car, but fans didn’t want it to drive off — they wanted to kill Costa on sight. Costa was eventually driven away, while the stabbed player was hospitalized and would later recover. The game itself was called off and officials set a new date for it to resume. However, Gremio refused to play, which resulted in them losing three points, costing them the Porto Alegre title.

In 1919, officials in Rio Grande do Sul decided to implement an official state championship, the Campeonato Gaucho (better known as the Gauchao). While the competition would become dominated by the Grenal clubs in the future, the first two titles went to Brasil de Pelotas and Guarany de Bage, respectively, though Gremio did finish runner-up both years. In 1921 though, Gremio broke through, going back-to-back the following year. Gremio could have won even more had Rio Grande do Sul not been halted by the Revolution of 1923, which canceled the next two seasons. Gremio would get another championship in 1926, after which Internacional finally got on the board in 1927. Gremio would get two more championships in the 1930’s, though Internacional also won another in 1934. Though the Gauchao had become the more prestigious title, the city championship still mattered — just look at what happened in 1935. Going into the final match of the season, Internacional had a one-point lead over Gremio, with the two facing off for the right to advance to the state championship. This particular season was also special because it was the centenary of the Ragamuffin War, giving the title an extra bit of flair. This game would also be the last for Eurico Lara, a goalkeeper who had been with Gremio since 1920 who had decided to return for one last year, despite dealing with cardiac problems. With the match still scoreless late in the first half, Internacional was awarded a penalty. The penalty taker, who just happened to be Lara’s brother, reminded the goalkeeper of the risk he was taking. Nevertheless, Lara made the save, though it cost him — those cardiac problems came back to haunt him, with some reporting him having a strike after the shot hit his chest. Lara was substituted at halftime and would pass away about two months later. Far be it for me to say whether or not one’s life is worth losing in the pursuit of greatness. What I will say is that Gremio would score two late goals to win the championship, with Lara being given the nickname “Immortal” and engrained in Gremio’s official anthem.

The 1940’s brought two things to Rio Grande do Sur: a “professional” designation to the state’s soccer scene and the “Rolo Compressor” (“Steam Roller”). The latter was the nickname given to Internacional, who, like the machine they were named after, flattened the competition. Back in 1926, Internacional started accepting black players into their squad (a decision Gremio would not make until 1952), which have them support that would come to fruiting about 15 years later. The results were simply insane — starting in 1940, Internacional won six Gauchaos in a row and 13 out of 16, with the last coming in 1955. While Gremio did get two championships of their own during this stretch, but they were largely reduced to second-fiddle at best during this stretch of Internacional dominance. This included the final game of the 1948 season, in which decades of waiting for revenge was paid off with a 7-0 victory by Internacional, the largest margin of victory against Gremio ever. It also surpassed a 1938 friendly that saw Internacional thrash Gremio 6-0, but also saw the referee annul five goals due to offsides calls/hand balls. In 1945, a 4-1 Internacional win came with a bonus greater than most victories could provide — Internacional officially overtook Gremio in goals scored in Grenal matches. To this day, this is the last time such a swap in the goal standings took place. Gremio did get one notable historic achievement, coming back from down 0-3 at halftime of a 1944 Grenal match to win 4-3 in the largest comeback in rivalry history. But even towards the end of the Steam Roller era, Gremio was second best. In 1954, Gremio inaugurated its brand new home of Estadio Olimpico Monumental with a four-team tournament. Gremio met Internacional in the final, with the latter winning 6-2.

In 1954, Renner would win the Gauchao — the next club not named Gremio or Internacional to do so would be Juventude, in 1998. That 44-year run of dominance by Grenal clubs began at the tail end of the Steam Roller era, but it would soon be filled with a return to form from Gremio. 12 out of 13 times from 1956-68 (including seven times in a row to end that run), Gremio came out on top in Rio Grande do Sul. That run also saw Gremio expand its horizons beyond their state’s borders. Although Internacional was literally named after being multi-national, Gremio traveled north for the first time in the 1950’s, heading to Mexico, Ecuador, and Colombia for a tour dubbed “the Conquest of the Americas.” In 1959, Gremio made history with a road win over Boca Juniors, becoming the first foreign team to beat them at La Bombonera. Two years later, Gremio went on its first European tour, playing 24 games across 11 countries, including France, Germany, Belgium, Greece, Denmark, and Russia. In addition, Gremio won the first ever Grenal match played outside of Porto Alegre, beating Internacional 2-1 in the Ipiranga Cup in the city of Rio Grande. The last entry in what Gremio fans refer to as the “Heptacameonato” came in 1968, one day after the club got revenge for the first Grenal at the Olympic stadium with a 4-0 win over Internacional.

While Gremio was achieving this notable success at home and overseas, when it comes to the newly-formed national Brazilian league, Gremio had yet to make a splash, though it had been semi-finalists a few times. The same could be said for Internacional, though they finished as runners-up twice at the end of the decade. As for the Gauchao, the pendulum was once again swinging back in Internacional’s direction. That includes the creation of a brand new stadium — the Beira-Rio — with construction beginning in 1956 (the start of Gremio’s reign) and the venue opening in 1969 (Internacional’s first championship season in eight years). That would be the start of eight in a row for Internacional, with the club getting more cracks at the Brazilian national championship. Finally, in 1975, Internacional became the first team from Rio Grande do Sul to become champions of Brazil, winning the league final thanks to the famous “Illuminated Goal” by Elias Figueroa. They would also become the first Rio Grande do Sul club to win back-to-back titles, repeating in 1976 before adding a third in 1979 (the last to this day for Internacional). Those championships would also get them cracks at the Copa Libertadores, with Internacional reaching the final of the 1980 edition, narrowly losing to Nacional 1-0. By this time, however, Gremio was starting to make a comeback, taking some Gauchaos for their own. In addition, Gremio made some Grenal headlines in 1977, first with Yura scoring the fastest goal in rivalry history (14 seconds into an eventual 2-1 Gremio win), then beating Internacional 4-0 at the Beira-Rio on a night in which Internacional had debuted a brand new uniform.

That sustained success would eventually pay off for Gremio, with the club finally claiming a Brazilian championship in 1981. However, it was actually the following season (which saw Gremio finish second place) that would lead to the greatest success. The club still qualified for the 1983 Copa Libertadores, getting past the team that had finished in first the year before (Flamengo) in the group stage before advancing to the final. There, they drew 1-1 with Penarol before a Cesar goal late in the second leg at Olympic stadium gave them a 2-1 victory and their first South American title. Gremio would also make it back to the final the following year, narrowly falling to Independiente by a 1-0 margin over two legs. But the 1983 triumph also gave Gremio a ticket to the 1983 Intercontinental Cup, which they won 2-1 against Hamburger SV. However, Internacional was in the middle of a four-year run as Gauchao winners at the time, so one of their players taunted Gremio by saying couldn’t even win their home state’s title. So a special match was held to put all the banners on the line — Gremio won 4-2. But even that was nothing compared to the hype surrounding what happened nearly five years later, when Gremio and Internacional met in the 1988 Brazilian Championship semi-finals. With the first leg at Olympic Stadium ending 0-0, everyone knew it would be all to play for at the Beira-Rio. Dubbed the “Grenal of the Century,” leg two saw Gremio jump out to a 1-0 lead and Internacional go down to ten men in the first half. However, Internacional would bounce back with two goals from Nilson (who was playing injured) to win 2-1.

In 1989, the first Copa do Brasil was held, with Gremio deciding they really liked that trophy. Gremio won the inaugural edition and narrowly lost to Criciuma in 1991. That wasn’t the only bad news, as a horrible dip in form led to Gremio being relegated for the first time. To make matters worse, Germio would be eliminated by Internacional on penalties in the 1992 Copa do Brasil, which the latter club would win for the first and only time. After making their way back to the first division, Gremio needed a new manager and found it in an ironic place: the other team that knocked them out of the tournament. Former Criciuma (and Gremio) manager Luiz Felipe Scolari was brought into the club, though he only stayed for three years. However, Gremio absolutely went off with Scolari in charge, winning the 1994 Copa do Brasil, 1995 Copa Libertadores, 1996 Recopa Sudamerica, 1996 Brazilian championship, and three Gauchaos. Although Gremio would win another Copa do Brasil immediately after Scolari’s departure (as well as a fourth in 2001), Internacional would bag a memorable 5-2 win over their rivals that same year. 1998, however, would be a surprise year for both clubs — for the first time since 1954, another club (Juventude), won the Gauchao.

Over the past two decades, Grenal has taken a step up, with both clubs not just winning international hardware, but beating each other in the quest for more. This began in 2004, when Internacional and Gremio met in the early stages of the Copa Sudemaericana, with the former holding on for a 3-2 aggregate win. The rematch would come four years later — while things would go to penalties this time, Internacional would win once again. This would become important when Internacional would go on to beat Estudiantes to win the whole thing. This would be the second of three international trophies for the club of the same name, spliced perfectly in between the first and third. Two years earlier, Internacional beat Sao Paulo to win its first Copa Libertadores title (and then beat Barcelona to win the FIFA Club World Cup). Four years later, Internacional doubled that count by topping Chivas (seriously). On top of that, Internacional went on another lengthy Gauchao roll, winning eight of nine titles (including six in a row) from 2008-16. But Gremio (who once again was relegated in 2004), still got its licks in during this time, including winning the 100th anniversary Grenal match 2-1 and recording the largest rivalry victory of the 21st century, topping Internacional 5-0 in 2015. Gremio also won its fifth and most recent Copa do Brasil in 2016, followed by the third and most recent Copa Libertadores in 2017. The following year, Gremio won the first of its current six straight Gauchao titles, coming within three of Internacional’s record. In 2020, a long-awaited scenario finally played itself out: Gremio and Internacional met in the Copa Libertadores. Naturally, things got a bit insane, and not just because the match ended with zero goals and eight combined red cards. It was the last Libertadores match before the COVID-19 pandemic suspended play for several months. When the two teams eventually took the field again, Gremio won the second match 1-0. After a while, fans would be allowed back in the stadiums, which would become a bad thing inn 2022, when the first ever cancellation and suspension in Grenal history would take place due to Internacional fans throwing rocks and metal pipes at the Gremio bus, injuring a player in the process. So don’t be fooled, Grenal is getting even crazier by the year.

MAJOR ON-FIELD MOMENTS:

TEN IN ONE

The first ever Grenal was the most lopsided result ever between the two rivals. The newly-born Internacional wanted to face Gremio, who just wanted to play their reserves. Internacional balked at the proposal, so Gremio fielded its top players and brought its “A” game. That would result in the largest margin of victory in Grenal history: 10-0. Edgar Booth scored five goals, while Julio Grunewald added four more and Gremio’s goalkeeper reportedly left the pitch in the middle of the match to chat with some fans. Things wouldn’t get much better for Internacional in the next two games against Gremio — 5-0 and 10-1 losses would soon follow. In fact, it would take seven matches over the first four years of the rivalry for Internacional to get that first win.

SOMEBODY’S GOTTA GET STABBED

The first ten Grenals were feisty, but generally went off without a hitch. Then came No. 11. With Gremio leading 1-0 in the 43rd minute, the ball went out of bounds, with there being a debate over who had possession. Suddenly, a fight broke out between Gremio fans and Internacional players, igniting a brawl that basically involved everyone. During the melee, a fan named Manoel Costa swung a knife around, threatening anyone who came near. An Internacional player tried to calm him down and got stabbed by Costa, who also injured one other player. Costa was eventually arrested, which was lucky given that the crowd wanted to kill him after that. The stabbed Internacional player was hospitalized and the match would be called off.

BECOMING IMMORTAL

In 1935 (the 100th year since the Ragamuffin War), Internacional and Gremio met with the Porto Alegre title on the line. With Internacional needing just a draw to clinch the crown, they were given a penalty in the first half. Standing in goal was Eurico Lara, a Gremio icon who had come back for a 15th season, despite suffering cardiac problems. His brother, a doctor who just happened to be Internacional’s penalty taker, reminded him of this, right before Lara saved the kick. It came at a tremendous cost — Lara was substituted at halftime and died two months later. Gremio would go on to win the match 2-0 and claim the championship. Lara, who has since been given the nickname “Immortal” has been immortalized in Gremio’s official anthem.

ROLLING OVER THEIR RIVALS

For more than 15 years, Internacional was the unquestioned best team in Rio Grande do Sul. During this time, they surpassed Gremio in terms of goals scored in Grenal matches, an honor they still maintain today. That stretch of goal-scoring prowess was helped by two huge ass-whoopings. In 1938, Internacional ran over Gremio to the tune of 6-0, though the score could have been even worse — the referee waved off five more Internacional goals, twice for hand ball and three times for offsides. Internacional would eventually get that seventh goal ten years later — in Gremio’s stadium no less. In the final game of the 1948 Porto Alegre season, Internacional absolutely thrashed Gremio 7-0 — the largest margin of victory for them over their rivals.

THE GREAT COMEBACK

During Internacional’s historic Steam Roller run, Gremio had little to celebrate. However, they did manage to record one historic moment over their rivals. Going into their August 1944 clash, Gremio had lost three Grenal matches in a row. It seemed like Internacional was going to make it four, when they went up 3-0 at halftime. However, manager Telemaco Frazao must’ve told the Gremio players some magic words in the locker room, because they came out for the second half on absolute fire. Two goals from Ramon Castro — along with a goal apiece from Bentevi and Mario — catapulted Gremio to an incredible 4-3 victory, a rare one in that era. The four-goal swing remains the largest comeback by either of the two rivals ever in a Grenal match.

UNWELCOME HOME

In 1954, Gremio inaugurated its new stadium, Estadio Olimpico Monumental, with a four-team tournament. In additional Uruguayan clubs Nacional and Liverpool, Internacional was invited to participate, which would end up being a bad idea for the hosts. In the first ever match, Gremio took care of Nacional 2-0, while Internacional followed that up with a 4-0 win over Liverpool. Thus, the third ever match in the stadium would be the first Grenal in the new venue. Gremio went up 1-0, but then Internacional woke up, scoring six straight goals (four of them coming from Larry (my new favorite Brazilian soccer player name) alone. Gremio got one back, but Internacional still walked out of their supposedly new venue of doom with an emphatic win.

FAST GOALS, CURSED UNIFORMS

1977 was the first big year for Gremio in terms of matches against Internacional in a long time. First, Gremio won their first Gauchao in nine years, breaking their rivals’ stranglehold on the competition. Then, two memorable Grenal matches went in their favor. First, Yura made history by scoring the fastest goal in Grenal history, putting the ball in the back of the net in just 14 seconds (without anyone on Internacional touching it). Gremio would go on to win 2-1. Five months later, Gremio went into the Beira-Rio, where Internacional was debuting a brand new uniform (the first all-red uniform in club history). In the end of the day, Internacional would be waving the white flag, as Gremio smacked them 4-0 to ruin the debut of the brand new kit.

BATTLE OF THE BANNERS

In 1983, Gremio won its first Copa Libertadores title and claimed the Intercontinental Cup. However, Internacional had won that year’s Gauchao, with Mauro Galvao provoking Gremo’s Renato Caucho, saying, “They may be world champions, but here in the state we rule. That caused Gremio’s Renato Gaucho to ask for a match to be played, with all of the honors on the line. In fact, when the two teams took the field, banners/sashes representing those honors were placed along the sidelines to be handed to the winners. In a great plot twist, Gaucho himself scored for Gremio, would wind up being victorious by a final count of 4-2, finally proving that the best club soccer team in the world was in fact the best in Rio Grande do Sul as well.

THE GRENAL OF THE CENTURY

The 1988 Brazilian Championship semi-finals saw arguably the most hyped Grenal in history. Of course, Gremio and Internacional drew each other and finished 0-0 in the first leg at Olympic Stadium. With everything (including a shot at the Brazilian title and a spot in the Copa Libertadores) to play for in the second leg, a huge Grenal crowd of 78,083 packed the Beira-Rio to see these two rivals face off. Things seemed to be going well for Gremio, who took the lead in the 26th minute and saw Internacional go down to ten men in the first half. However, in spite of that adversity, Internacional came roaring back in the second half thanks to two goals from Nilson, who was playing injured. Internacional won 2-1, though they fell in the final.

BRAZILIAN CUP BATTLES

The first (and only) two Grenal matches ever to take place in the Copa do Brasil happened in 1992. However, there technically has yet to be a winner, or even a team to score a goal in the first half. The first leg saw Internacional answer a Gremio goal to finish in a 1-1 draw. The second leg saw Gremio answer an Internacional goal to finish in a 1-1 draw. Yep, two games, two draws of the exact same scoreline. But because this is a tournament, someone had to advance. Penalties were needed, which spelled doom for Gremio. One kick went over the bar and two others were saved by Fernandez, with only three successful attempts needed for Internacional to advance to the next round and eventually win the whole tournament.

AN EVENTFUL MATCH

When two groups of eleven players combine to create a third starting lineup composed solely of goals and red cards, shit definitely went down. That was the case in 1997, when defending Copa do Brasil champs Gremio met defending Gauchao champs Internacional. After an opening goal from Internacional, the goal scorer and a Gremio player got into a fight and were sent off. Another fight led to another player from each team being tossed, sending both squads down to nine men. Mind you, all of this happened within the first 30 minutes of action. The remaining hour saw a rate of a goal every ten minutes. Unfortunately for Gremio, most of those goals were scored by Internacional, who came out on top 5-2 in an incredibly eventful affair.

RONALDINHO’S BREAKOUT PARTY

Dunga is one of the most respected Brazilian soccer players ever, both nationally (he captained the 1994 World Cup-winning squad) and in Porto Alegre (beloved by Internacional). However, on one fateful day in 1999, he would be made the bitch of a generational player who would surpass him in every way. That day, Internacional and Gremio met in the third and final leg of the Gauchao final, with the latter sporting a 19-year-old wonderkid named Ronaldinho. In addition to scoring the only goal of the match, Ronaldinho embarrassed Dunga to a drastic degree, flicking the ball over his head on one occasion and leaving him flat-footed on a crazy dribble on another. Ronaldinho left with a victory and a trophy; Dunga got his ankles broken.

SUDAMERICANA SHOWDOWNS

It took nearly a century (though to be fair, these tournaments didn’t exist for half that time, but in 2004, Gremio and Internacional took their rivalry… international. Their second round matchup produced the first two Grenals to take place in continental competition. In keeping with the theme, Internacional won 2-0 in the first leg and held on in the second leg to win the tie 3-2 on aggregate. The next international match came a whole four years later in the same competition. This time, both legs ended in a draw, with the aggregate score being 3-3. Unfortunately for Gremio, the away goals rule was in play here. So the 2-2 draw in Gremio’s stadium ended up being the decider, which was pretty crucial for Internacional, who would win the tournament.

THE 21ST CENTURY ROUT

Ever since embarrassing Internacional by a combined score of 25-1 in their first three matches, Gremio had yet to truly rout their rivals, who had gotten some ass-whoopings of their own in. Over a century later, Gremio’s long wait finally came to an end. This 2015 match was a dominant showing by Gremio, though the first goal didn’t come until the 35th minute. Luan only waited seven more minutes to add a second, then waited just two minutes into the second half to add a third. A fourth goal was added in the final 15 minutes, with an Internacional own goal completing the humiliation. The 5-0 scoreline remains the largest margin of defeat in a Grenal match in the 21st century, as well as during the professional era (dating back to 1940).

COPA LIBERTADORES CHAOS

It took until literally the last match before the COVID-19 pandemic, but Internacional and Gremio finally met in a Copa Libertadores match in 2020. Naturally, the rivals had to make up for lost time. Although the first leg ended 0-0, it featured one of the craziest endings in Grenal history. A shoving and shouting match in the final ten minutes led to four red cards — then a mass brawl broke out and four more red cards were issued, with both teams finishing with eight men on the field. Because of the pandemic, it would be another six months before the second leg could be played. That match (and the tie as a whole) saw one more goal than the amount of fans in attendance, with Gremio winning 1-0 thanks to Pepe, in his 100th game for the club.

PRE-MATCH ATTACK

For a rivalry that’s nearly 115 years old, to have a “first” of any kind is a rarity. But such a first indeed happened just over a year ago. Despite all of the violence and animosity between the two rivals, a Grenal match had never been outright canceled and postponed. On February 26, 2022, Gremio’s team bus was on its way to the stadium when a group of Internacional fans attacked it with rocks and iron bars. Several rocks managed to break the bus’ windows, with one rock hitting Mathias Villasanti, who was hospitalized with a concussion and other head trauma. While this would be the first Grenal match to ever not even kick off, it would eventually take place — it was rescheduled for March 9, with Internacional coming out on top 1-0.

STATISTICS:

HEAD-TO-HEAD RECORD

Gremio: 141

Internacional: 160

Draw: 138

LEAGUE CHAMPIONSHIPS

Gremio: 2

Internacional: 3

COPA DO BRASIL

Gremio: 5

Internacional: 1

SUPERCOPA DO BRASIL

Gremio: 1

Internacional: 0

CAMPEONATO GAUCHO

Gremio: 42

Internacional: 45 (record)

COPA LIBERTADORES

Gremio: 2

Internacional: 2

COPA SUDAMERICANA

Gremio: 0

Internacional: 1

RECOPA SUDAMERICANA

Gremio: 2

Internacional: 2

FIFA CLUB WORLD CUP

Gremio: 0

Internacional: 1

INTERCONTINENTAL CUP

Gremio: 1

Internacional: 0

NOTABLE FIGURES:

MANOEL COSTA

What do you have to do to become a notable figure in a major sports rivalry despite neither playing nor coaching for either team? For Manoel Costa, an employee of the Rio-Grandense Telephone Company, he channeled his inner Raiders fan. When a fight broke out during a 1918 showdown between Internacional players and Grenal fans — which sparked a pitch-wide brawl — Costa wound up stabbing a member of Internacional and slashing another player. Costa was arrested, although fans nearly prevented the police car from leaving, as they wanted him dead.

EURICO LARA

Having been with the club since 1920, Eurico Lara was already a Gremio icon before he decided to return for one more year in 1935, despite cardiac problems. With Gremio needing a win over Internacional to be Porto Alegre champions, Lara was put on the spot when Gremio was called for a penalty. He managed to make the save (against his brother, no less), but had to be substituted at halftime. He would tragically pass away just two months later. Lara, known to Gremio fans as the “Immortal,” was later included in Gremio’s official anthem and is there today.

CARLITOS

When Internacional dominated Rio Grande do Sur during the Steam Roller era, Carlitos was the one largely behind the controls. With 483 goals, Carlitos remains by far the highest-scorer in Internacional’s history, providing plenty of ammo for the club’s record-setting offense in the 1940’s. Carlitos had a particular skill of scoring against Gremio — his 40 goals are by far the most by any player in Grenal history. Fun fact: Carlitos believed his legal name was Carlos until he was 16 — he gave his birth certificate to Internacional and discovered he was really Alberto.

LARRY

Speaking of names, Larry might be my new favorite Brazilian soccer player name, though it has to get past Hulk. But with all due respect Larry was a phenomenal striker, forming a partnership with fellow forward Bondinho to form an incredibly potent scoring duo for Internacional. Larry joined Internacional in 1954, two years after being Brazil’s top scorer in the Summer Olympics. Larry soon endeared himself to his new fans by scoring four goals against Gremio in just the second Grenal he played in. Larry scored more than 175 goals in 260 games for Internacional.

ALCINDO

Alcindo began his youth career with Internacional at age 13, but was later dismissed after reportedly asking for an allowance to go to training. He would soon join Gremio, who didn’t fumble the tremendous talent it had. Although Alcindo didn’t stay with Gremio for his whole professional career, he still became a club icon by scoring a lot of goals. In fact, Alcindo remains Gremio’s all-time leading goal-scorer with 264 balls in the back of the net. Alcindo is also Gremio’s second-highest scorer in Grenal, trailing only Luiz Carvalho, who tallied 18 goals.

HECTOR SCARONE

When Gremio broke Internacional’s grasp on the Gauchao and later won the Brazilian league title, Copa Libertadores, and Intercontinental Cup, Tarisco was the driving force behind the tricolor revolution. In addition to being a great winger who helped power some of Gremio’s best ever squads, Tarisco stuck around long enough to set the all-time record for most appearances in a Gremio shirt (721). He also tallied a lot of goals (226), finishing second to Alcindo for most in club history. Tarisco would later have a notable career as a politician in Porto Alegre.

VALDOMIRO